Tom Toomey has worked in the apartment industry for 30 years, spanning the tech bust of the early 2000s, the housing bubble of the mid-2000s, the global financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic.

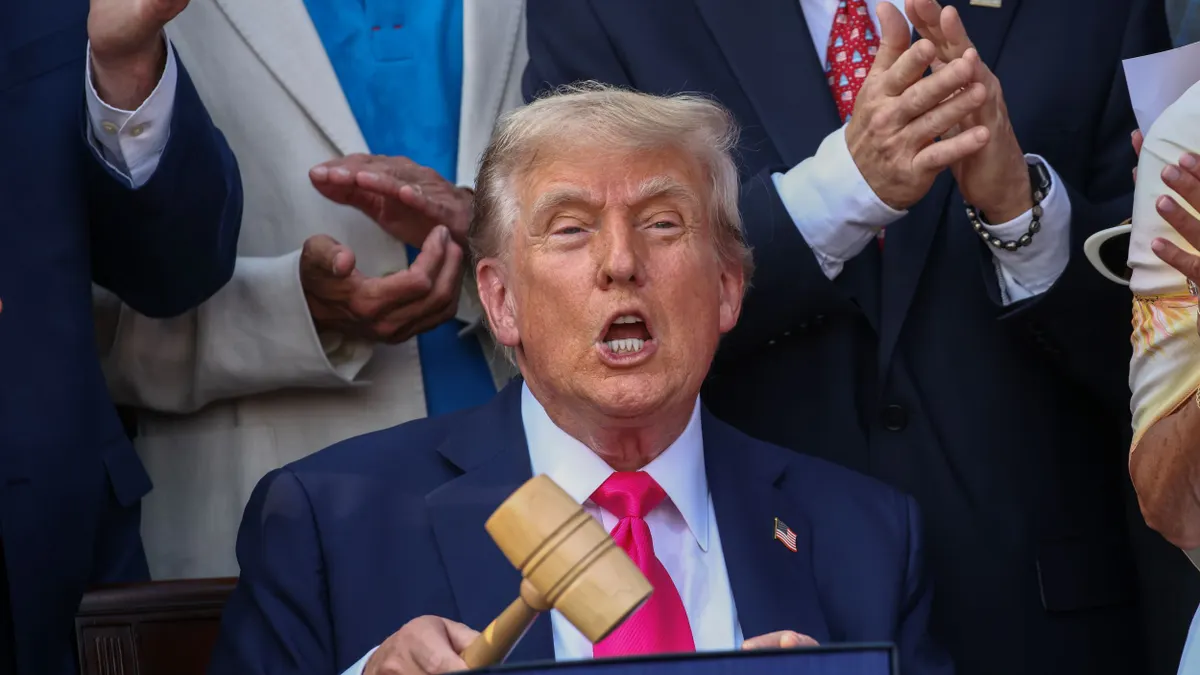

But this fall, something started happening that even the veteran UDR CEO had never seen before. Merchant developers began dropping prices and offering concessions on their newly built apartment buildings, putting pressure on older properties that normally don’t compete with new supply.

“This dynamic and its impact on our B-quality communities, in particular, was unexpected and unprecedented in my 30 years in the multifamily industry,” Toomey said on the Highland Ranch, Colorado-based REIT’s third-quarter conference call.

Toomey isn’t alone in seeing this trend. Other apartment owners and industry analysts have been surprised by the trickle-down effect of concessions on class B portfolios in high-supply markets. Nevertheless, many expect the impact to be short-lived.

Treasury impact

Deliveries of new apartments have increased over the past year. But in the third quarter, things accelerated. In a recent report, Zillow said that 30% of rental listings had at least one concession in October, compared to 24% a year ago and 25% in June. That was the highest figure since June 2021.

Why did concessions jump so quickly? The answer lies with Treasury bonds, according to executives at Memphis-based REIT MAA on the company’s recent earnings call.

When the 10-year approached 5% in October, it extinguished the hope that interest rates would come back down anytime soon. Builders suddenly felt pressure to hit 90% occupancy by the end of the year in order to sell or put permanent financing on their buildings.

“I think [lease-up pressure] has just been a little bit more intense because of what's going on with the interest-rate environment,” MAA CEO Eric Bolton said. “And therefore, it's manifesting itself in more competitive pricing practices in an effort to attract new residents and leasing traffic.”

Up to three months free

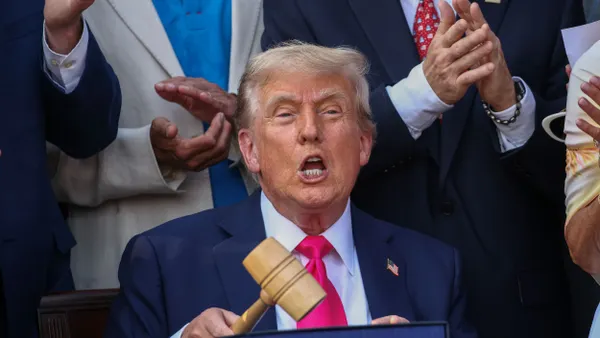

Right now, Camden Property Trust CEO Ric Campo sees peak concessions of three months in markets like Nashville and Austin, Texas, where new supply is as high as 6% of inventory. In other Sun Belt markets, like Charlotte, he sees developers offering four to six weeks of free rent.

“There’s an old joke in the merchant builder world that you don’t want to be the last one on the street to get to three months free,” he said on the Houston-based REIT’s third-quarter earnings call.

Once a free rent promotion gets to three months, that is 25% off of a 12-month lease, making a brand new apartment look like a good deal for many consumers.

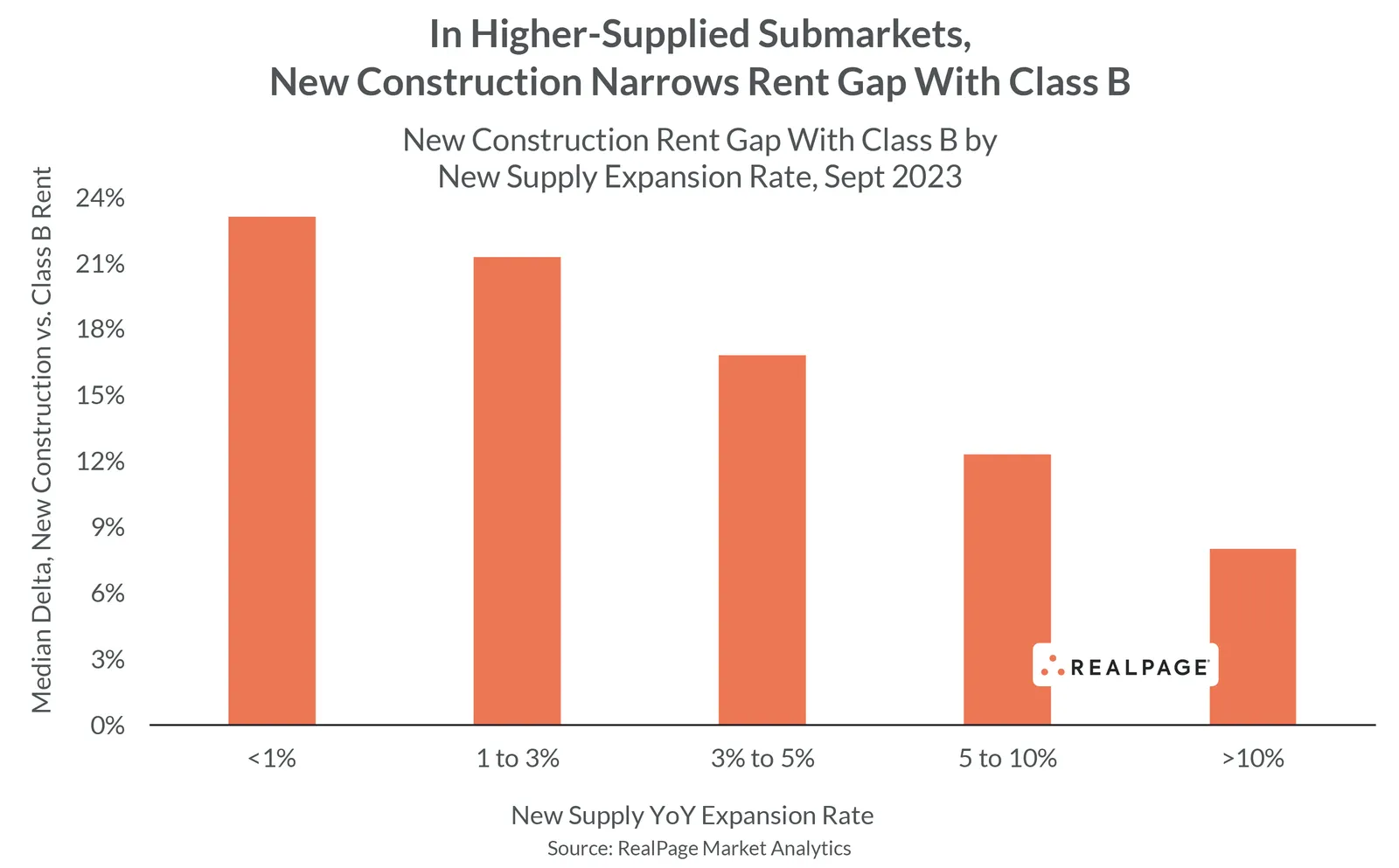

“When these lease-ups are offering two- and three-month concessions, that's bringing their rents pretty close in line with the existing market,” Jay Parsons, senior vice president and chief economist, at RealPage, told Multifamily Dive.

For a renter living in a building that’s 10 or 20 years old, those concessions can suddenly make moving up a level in asset class affordable.

“If there's a brand new lease-up that's more amenitized and nicer, and it only costs 5% or 10% more after the concession to go in there, the renters are thinking, ‘I'm going to pay a little more, but I can afford it,’” Parsons said. “Obviously, not everybody can, but there's a group that can, and that's actually pulling people out of class B and A-minus properties.”

An ‘unexpected twist’

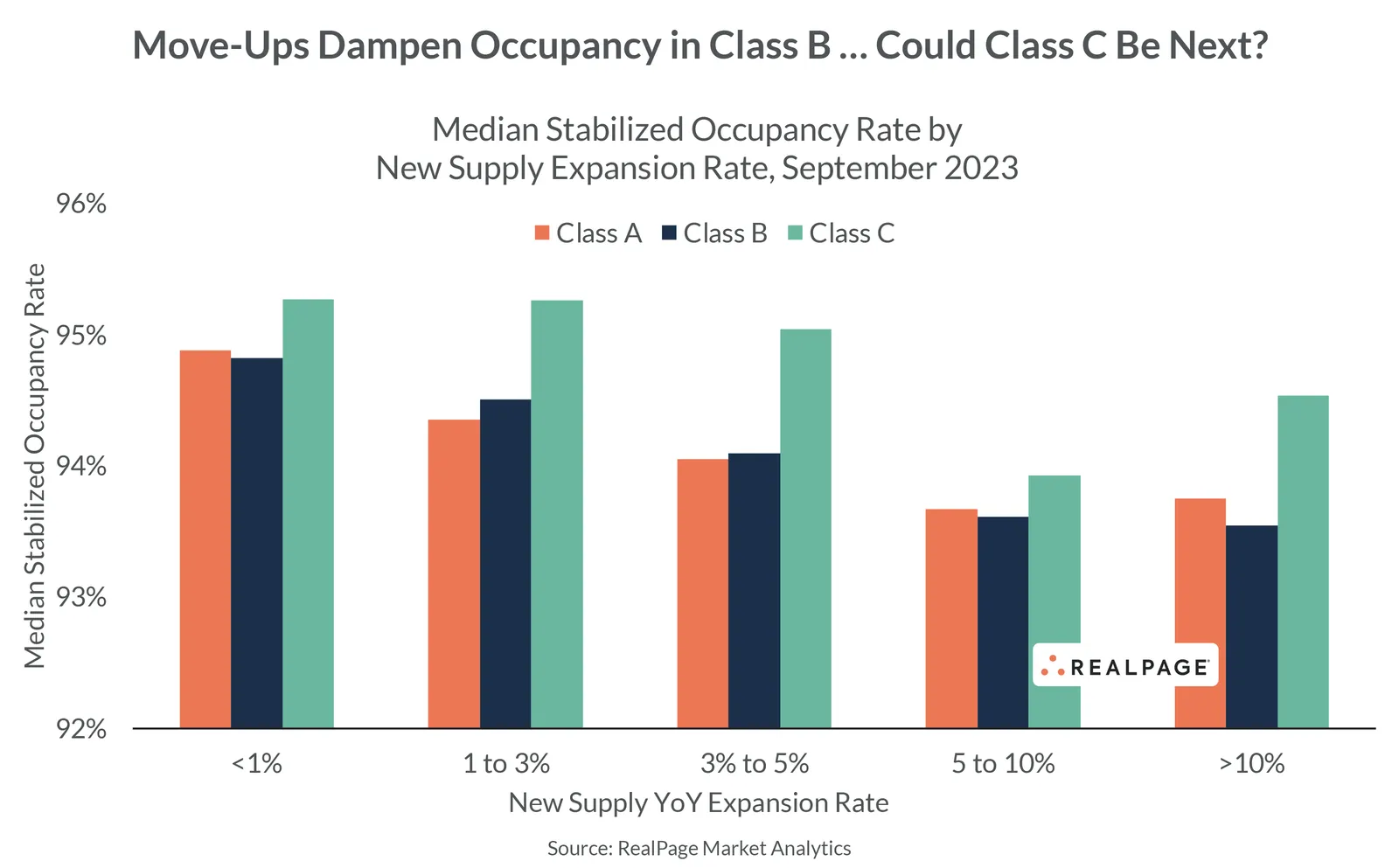

In submarkets where apartment unit counts have expanded by 10% or more in the 12 months ending September 2023, effective class B rents fell 3.7%, according to a RealPage article that called the trend the “most unexpected twist” in multifamily this year. By comparison, class A rents dropped 1.5% and class C rents fell 0.8%.

In submarkets where supply increased 5% to 10% in the 12 months ending September 2023, rents fell 2% in class B. In class A, they dropped 0.6%, and they declined 1.5% in class C.

These trends were amplified on the recent REIT earnings calls. For UDR, A’s outperformed B’s in new lease growth by about 170 basis points, according to Mike Lacy, senior vice president of operations at the company.

“This is very different from what we experienced during the second quarter and, quite frankly, what we would have expected to experience,” Lacy said. “During the second quarter, B’s actually outperformed our As on our new lease growth by 110 basis points.”

The silver lining

Price cuts have obviously hurt class B apartments. But the move-ups wouldn’t happen if renters couldn’t afford them.

For UDR, the traditional rent difference between new deliveries and B properties is 20% to 30%. With concessions, that delta has shrunk to 10%, which is about $250 per month.

“You're seeing the consumer say, ‘I can afford $250 [in] incremental [rent] a month,’” said Joe Fisher, UDR’s president and chief financial officer on the Q3 earnings call. “So, it speaks to the strength, cash position and kind of wherewithal for them.”

RealPage figures put the median rent-to-income ratio at 23%, showing that many renters have enough income to pay $200 more a month if they see a brand-new property in a good location with better amenities. “All of those things are attractive to those middle- and upper-income renters who could afford that,” Parsons said.

Although new supply is giving renters a chance to move up and a much-needed break from price hikes of the last few years, it won’t cure all of the nation’s housing and affordability issues. In some places, it's just providing a short-term reprieve.

“This is a short-term supply-demand imbalance,” Parsons said. “We’re going to build 1 million units between this year and next year. And it’s just hard to generate that much demand in that short period of time. But, eventually, that demand will catch up.”

Click here to sign up to receive multifamily and apartment news like this article in your inbox every weekday.