With fewer projects breaking ground and less demand for parcels to build on, it would make sense that landowners might back off their pricing demands.

Construction loans have been increasingly difficult to secure over the last couple of years, and many equity providers have also pulled back from the market. As a result, apartment starts have cratered, most recently dropping 21.8% year over year to a seasonally adjusted rate of 363,000 in July.

But prices are only dropping in certain instances, experts tell Multifamily Dive. In fact, many developers haven’t seen costs budge that much yet.

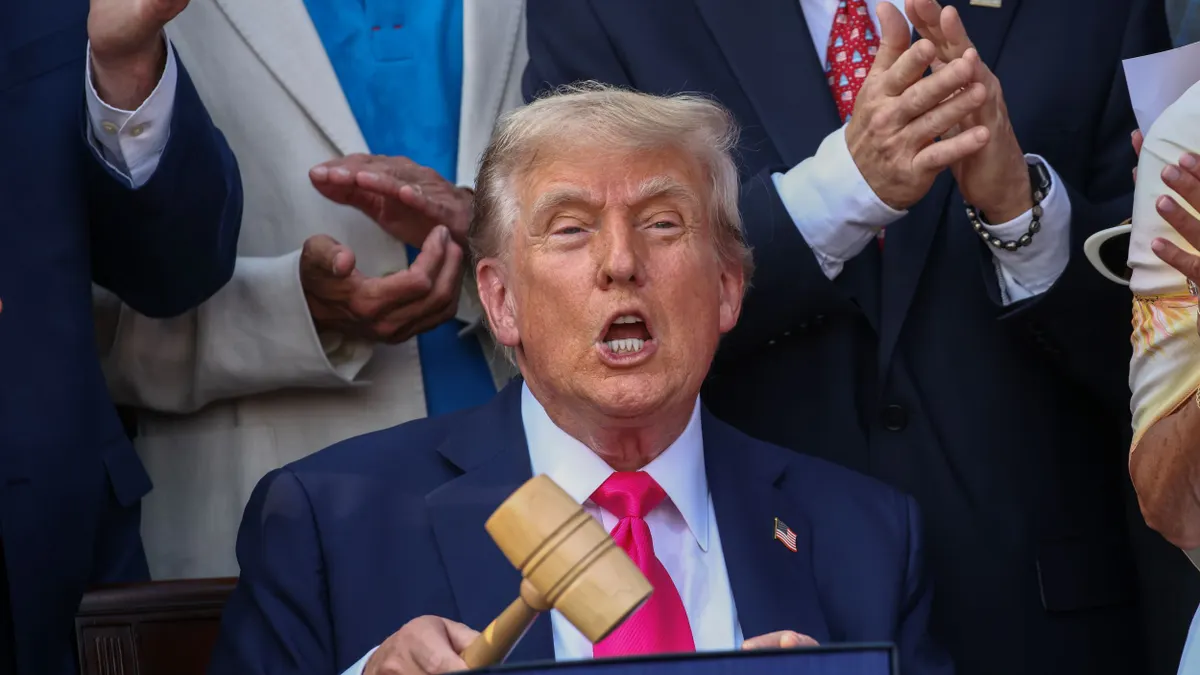

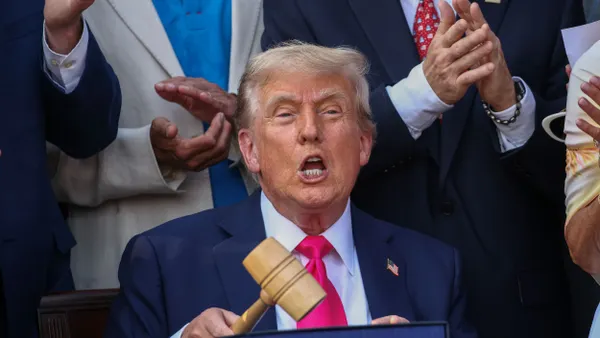

“Land is an interesting thing because it doesn't move as fast as you would think,” Ric Campo, CEO of Houston-based Camden Property Trust, said on the REIT’s recent earnings call. “The sellers, just like the sellers of existing apartments, are unwilling to drop their prices.”

But not all landowners are the same. Like everything in real estate, there are regional variations in costs. In addition, finding comprehensive pricing information for multifamily parcels is difficult, with many single-family data providers unable to produce apartment data.

The seller's financial position may play an even bigger role in whether a price cut is on the table. Long-term holders are in a position to sit and wait, while those who have recently purchased the dirt may be more motivated to make a deal.

“Where the opportunity can be — and we've generally seen this in past cycles — is that you have developers who own land who have been positioning to start the development, and they can't start the development because the debt and equity markets won't allow it today,” Campo said. “And so… they write off their soft costs, and then they sell the land.”

A largely stable market

In the early- and mid-2000s, cheap debt caused bubbles throughout the real estate market, whether single-family, condominiums or land.

“In the great financial crisis, there was a lot of leverage in land positions and across the market,” said Greg West, CEO of ZOM Living, an apartment developer based in Orlando, Florida. “That leverage created a great deal of stress in that market at that time.”

But that taught investors a lesson: Don’t pile debt on land positions, which won’t produce the monthly cash flow that a built property will. “The amount of leverage in the land positions has really changed,” West said. “There's not nearly what it was back then. So I think that has created more stability in that market.”

West said that discipline among landowners has kept prices from falling for 15 years now. The National Association of Realtors’ 2023 Land Market Survey showed the value of commercial land increased 1.8% in 2023 after jumping 6% in 2022. Residential land ticked up 2.9% in 2023 after soaring 10% in 2022.

If a land seller doesn’t have time sensitivity, they’re holding out for the price they want.

“Some [people] have had land in their family for several generations,” said Blake Schroeder, executive managing director of multifamily at Leon Capital Group, a Dallas-based holding company that owns, manages and develops apartments. “They've got a number in mind, and that's their number.”

Scott Maddux, CEO of Westlake Village, California-based rental housing developer and operator Sunstone Two Tree, found this out firsthand in 2021 when he bought a 29-acre lot in Glendale, Arizona. Sunstone Two Tree closed on the parcel in late September 2023 and is building a 320-unit rental community.

“We bought this piece from a farmer that had owned it for multiple decades,” Maddux said. “He was happy to just kind of hang out until the right guy came to pay the price that he felt was fair.”

Although many long-term landowners may not be budging on price, they are being more flexible and adjusting in other ways, according to Greg Bonifield, founder of Charleston, South Carolina-based apartment developer Woodfield Development.

“We’ve certainly seen landowners be more willing to work with us and give us time to put our capital together,” he said.

Developer deals

Long-term holders like farmers may not be willing to lower their asking price for dirt because they’re not under pressure. But apartment developers are a different story. They’ve been sitting on land waiting for financing. However, many can’t carry those costs forever.

David Laube, principal of Atlanta-based Noell Consulting Group, hasn’t yet seen scrambling and selling land for discounts. “I wouldn't say we're starting to see pain yet,” he said.

However, Laube is starting to see developers who might have seven deals under contract and are only getting debt on a couple of projects. “They might only get two of those financed,” he said. “So what are the two we really want to place our bets on?”

Schroeder has seen several shovel-ready opportunities where developers have projects entitled but can’t get them capitalized. “You hear of developers that are looking to flip out of land positions,” he said.

The financing delays can also create a sense of urgency for a landowner that controls a piece of dirt that a developer had entitled and previously controlled under options.

“The developer spent six months, dropped it and [the land owner] is getting fatigued,” Schroeder said. “They have been dropped and they need the certainty of closing.”

In these cases, Leon has been able to come in and buy that land with the company’s balance sheet. “We’ve acquired that land at a really good basis just because that seller needs to get out of that position,” Schroder said.

Regional differences

Seller motivation may be the main factor governing whether they’ll negotiate on land prices. But the location also plays a role.

“It varies, obviously, a lot by region,” said Matthew Birenbaum, AvalonBay Communities' chief investment officer, on the Arlington, Virginia-based REIT’s Q1 earnings call in April. “In some regions, particularly in some of our established regions, we have seen land prices come down significantly for motivated sellers.”

In AVB’s core coastal markets, prices have come down. For instance, the REIT secured land for 40% less than it had been previously priced at for a project in the Boston suburb of Quincy, Massachusetts, Birenbaum said on the Q1 call.

But in AVB’s Sun Belt metros, costs have only moved minimally. “In many of the expansion regions, the land is a much smaller percentage of the total deal cap than it is, say, in California or New York where land might be 30%, 40% of your total deal cap,” Birenbaum said.

On the other hand, in a place like Charlotte, North Carolina, land might only be 10% of the cost of a garden-style project.

“It's not going to move the needle as much, and it's not going to be as sensitive really in either direction,” Birenbaum said. “Land prices tend to be sticky in general, but they've probably been stickier in those markets where they were cheaper to begin with.”

But Sun Belt states have seen land costs skyrocket after COVID-19 hit. In Florida, where it has become very expensive, pricing is improving—a bit, according to Birenbaum. “We haven't necessarily seen significant moves down in land costs,” he said.

Click here to sign up to receive multifamily and apartment news like this article in your inbox every weekday.