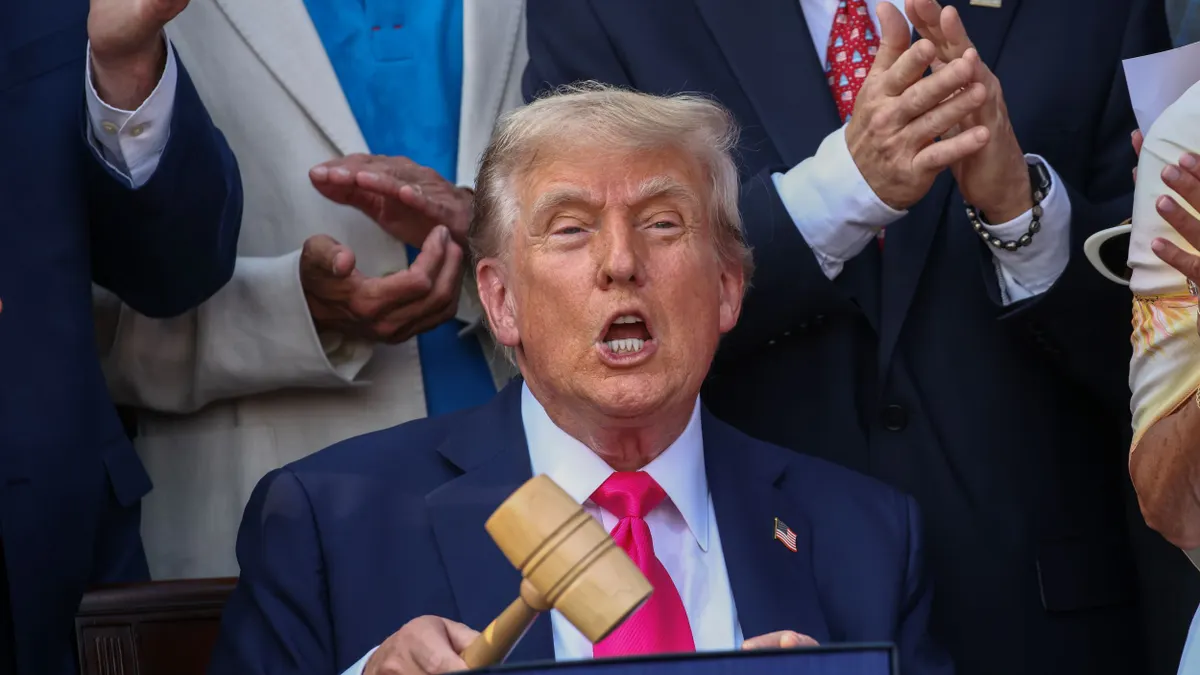

When Mark Alexander got 42 Broad — a 16-story, 249-unit building project in Mount Vernon, New York — to the finish line in July, you couldn’t blame him if he felt a great sense of relief.

“42 Broad really turned into a much more challenging construction project than we had planned for and anticipated,” the founder and principal of New York City-based Alexander Development Group told Multifamily Dive. “We're thankfully at the tail end now. And the product is coming out beautifully. But there were some challenges to get here.”

As the project began leasing last month, it came with one significant first. It is the largest market-rate multifamily high-rise to be certified to Phius Passive building standards. The project, located just north of the Bronx in Westchester County, is projected to use up to 80% less energy for heating and cooling than existing buildings, which should dramatically lower utility bills, and will continuously provide filtered and tempered fresh air.

Producing impactful real estate is nothing new to Alexander. He helped establish Hope Community Inc., a Harlem not-for-profit, community-based organization, in the late 1970s. He helped the organization triple its portfolio of mainly affordable housing assets from around 400 apartment units to more than 1,300 units in 10 years.

After starting Alexander Development Group in 2004, he has produced around 900 units in the New York City metro area — a notoriously tough place to build.

Here, Alexander talks with Multifamily Dive about overcoming legal challenges, incorporating energy-efficient features in development and the decision to pursue the Phias Designation.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

MULTIFAMILY DIVE: What were the challenges in building 42 Broad?

MARK ALEXANDER: Several events, including COVID-19, prolonged construction. So we're just about five years into construction at this point, which is a very long time to build an apartment building.

The approvals process from start to finish took about two years altogether, which is actually not too bad for Westchester County. But that got extended by another almost two years because of Article 78 legal challenges [a type of lawsuit used to challenge actions by New York state and local government agencies], which were meritless but still succeeded in slowing down the project.

So we were essentially in a pre-development phase for almost four full years, two of which were just spent fighting and winning legal battles.

Are those legal battles common in the New York metro area?

It's not typical of normal-sized housing developments. If this had been maybe a three-phase, 1,500-unit project, one would expect multiple challenges. But for a one-building, 249-unit project, you wouldn't expect the amount of challenges that we had.

But there hadn't been any real market-rate development in Mount Vernon of scale for decades. The only real large-scale housing development that's going on in Mount Vernon is affordable housing, which rarely is challenged. But market-rate development, which is oftentimes challenged, they just haven't done it. People weren't used to it.

What concerned people about it?

Some people thought it was a Trojan horse and we were really not going to market rate, that we're really just going to build a building that would get converted to Section Eight or homeless housing. There were all kinds of weird reactions. But at the end of the day, they were all process-oriented challenges. And since we followed the process assiduously and did all of our environmental and other submissions, they failed.

But the process takes time. The process won anyway, at least in terms of not killing us with delays.

What energy-efficient features did you want to include in 42 Broad?

A lot of newer luxury communities in the New York metropolitan area use PTAC [packaged terminal air conditioner] units. A PTAC unit is the typical unit you'd find in a hotel room. There's a box near the window and the air conditioning and heating are in that one box. There's a louver on the outside that allows fresh air to enter the unit to cool it off in the summer or provide fresh air at other times. Those units are really pretty cheap to install, but they're expensive to operate. They're not very energy efficient.

So we decided from very early in the design process that we wanted to build something that was more energy efficient. We took advantage of two different things. One was split systems — variable refrigerant flow systems. A refrigerant flows through the tubing into an air-handling unit inside the building. And those are inherently more efficient than the PTAC units.

The second big decision we made early on was to use insulated concrete formwork to build the superstructure. The big advantage is that while it's a more time-consuming method of construction, it's cheaper and it ends up with a much more energy-efficient enclosure.

How did the Passive building designation come about?

Once we were approaching the start of construction, J.P. Morgan Asset Management had signed on as our equity partner. They, for institutional reasons, wanted us to go through LEED. I think LEED-Silver was the minimum that we could achieve to satisfy their institutional requirements.

When we looked at the imperative cost and benefit of going to Passive house, we realized that it was not a whole lot of extra money from a hard-cost perspective, and somewhat less money for administrative, paperwork and consulting than is needed to get these certifications. Passive house would give us an even better, energy-efficient product in the marketplace. It would be unique in the marketplace, which might also be helpful in terms of marketing and the ultimate value of the building.

And then finally, it would be a somewhat more predictable process and somewhat less cumbersome process than going for LEED. So for a relatively modest amount of additional money — less than $1 million additional hard costs — we made the decision to switch from LEED to Passive house.

Click here to sign up to receive multifamily and apartment news like this article in your inbox every weekday.