Indianapolis-based Flaherty & Collins Properties broke ground in September on phase two of a $67 million, 409,000-square-foot mixed-use project in Mishawaka, Indiana, featuring 226 luxury apartments, 422 parking spaces and 10,600 square feet of commercial retail, including the city’s first riverfront restaurant along the St. Joseph River.

As Mishawaka Mayor Dave Wood said in the press release announcing the project, the purpose of The Mill at Ironworks Plaza is to increase economic development efforts in Mishawaka and “provide more opportunities for businesses, residents and visitors.”

The town has seen growth in manufacturing jobs from employers like local plastics producer MAKS Plastic and South Bend-based military contractor AM General.

The city made a major investment to get the Mill project off the ground. Mishawaka officials provided a 25-year tax increment financing district, issued bonds to support the development and donated the land. Phase two, which is slated to welcome commercial and residential tenants in spring 2025, includes a $6.3 million regional development tax credit from the Indiana Economic Development Corporation.

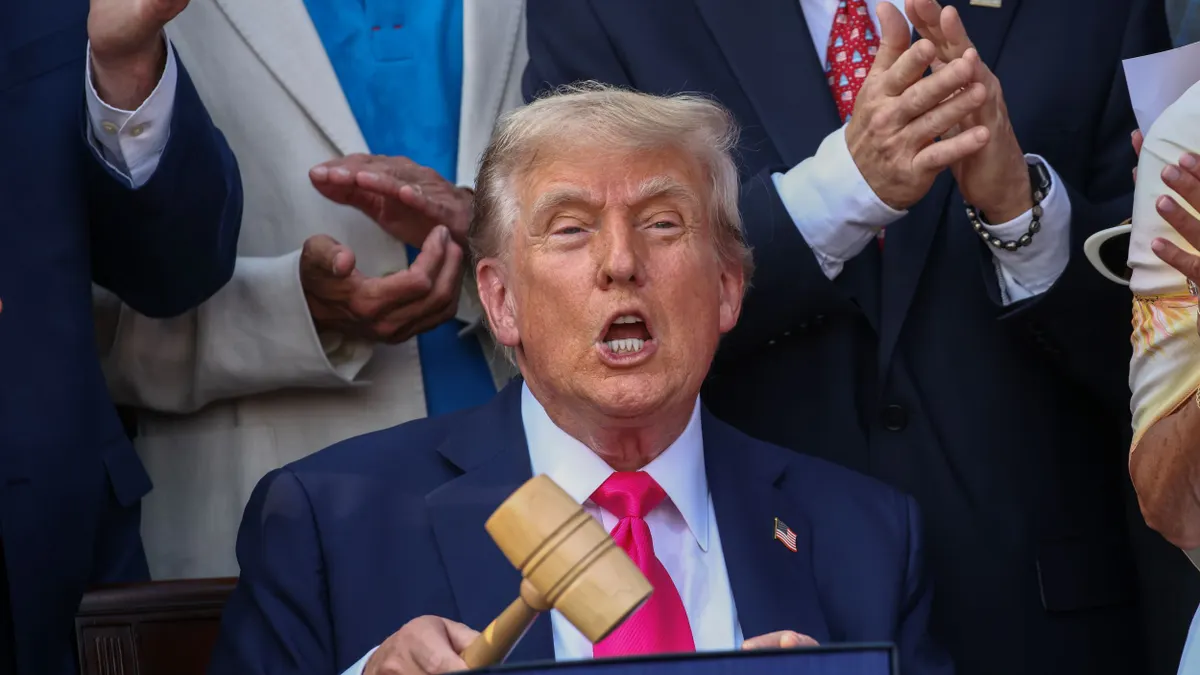

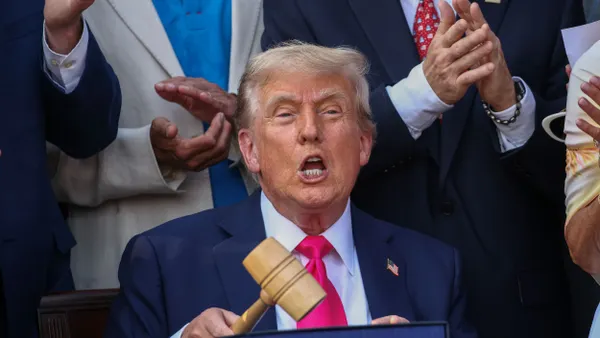

Flaherty & Collins has developed over 10,000 units that it owns and has 7,000 units under management, and its “bread and butter” is public-private partnerships, vice president of development and lead project developer Brian Prince told Multifamily Dive. The company has completed these types of projects in Cape Coral, Florida; Columbus, Ohio; and Kansas City, Kansas.

Here, Prince talks with Multifamily Dive about the impact of The Mill at Ironworks Plaza, the incentives offered by localities and what happens when public-private partnerships don’t work.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

MULTIFAMILY DIVE: I know phase one of The Mill at Ironworks Plaza has a waiting list. Were you able to attract newcomers to the development?

BRIAN PRINCE: Thirty percent of the people who lived in phase one were new to the state of Indiana as a whole. And 80% of the people were new to that city. So there wasn't a reshuffling of the deck or someone from across the street or down the road moving into the project. These are net new bodies. This is true economic development — bringing in people with higher disposable income to support the local businesses and the retail takes off.

Who are your renters at the project?

Notre Dame Stadium is three and a half miles from the site. So we have a mix of some grad students from Notre Dame who live at the property, as well as international professors who come from other countries.

The goal of the property is not only talent attraction and retention but also business recruitment. In order to recruit the businesses, you have to have a housing solution for the demographic they're going after. That allows the businesses to compete for talent. So it's all full circle. This story is more than just about slapping up apartments. It's about how we stop the brain drain and then get growth in our Indiana regional communities.

What incentives are the localities providing for you?

Indiana has a couple of tools at the state level, in addition to the local level. From a municipality standpoint, the usual tool is our tax increment financing generated from the project itself.

Our site is a municipally owned site, so there are no taxes being generated on that site right now. We come in and we'll usually commit to a taxpayer guarantee to get the city to either issue bonds or we'll purchase our own bonds.

Are there tools to help these projects pencil out?

We'll get our tax increment financing for the project and the city may throw in land. But then usually with these very complicated mixed-use dense projects, there's still an additional gap after that. So then you go into the state.

Indiana has what's called a regional development tax credit and they also have a program called READI [Regional Economic Acceleration and Development Initiative]. And through these two programs, the state incentivizes regions with dollars. Then those regions, which they call the Regional Development Authority, can dictate where they would like to place some of these dollars to help projects move forward.

Are there places where these developments won’t work?

There’s the comment, “Build it and they will come.” That can get you put out of business.

You have to have other factors in that market for someone to live there. You can fill up a building anywhere, but the question is: at what price point? You may underwrite $2,000 a month in rent for these units. Well, that's fine. But if those kinds of jobs aren't in that community that pay salaries that allow people to pay $2,000, it's irrelevant. You can fill that building up if you drop the rent down to $1,000 a month per unit.

There are communities around the state where we’ve done these exercises and a lot of times it’s a funding challenge. The gap is so big because rents are depressed in that community. Nothing has been built in 25 or 30 years and they want big, sexy and shiny.

But in order to make those numbers work, the rent has to be up here. I’m going to underwrite it to where I think the rents actually are achievable in this market. And that makes the project not feasible or it's a nut too big to crack right on the city and state incentives side.

Click here to sign up to receive multifamily and apartment news like this article in your inbox every weekday.